"Minipress 1mg otc, antiviral detox".

By: Y. Bradley, M.B. B.CH., M.B.B.Ch., Ph.D.

Clinical Director, Tufts University School of Medicine

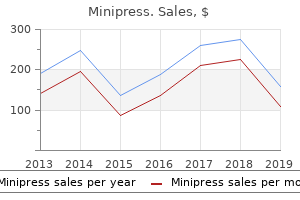

This phenomenon antiviral used for h1n1 generic 2 mg minipress free shipping, which is known as a phosphene hiv infection joint pain buy minipress australia, is the visual perception of flickering light hiv symptoms days after infection discount minipress 1 mg. The traversal of a single hiv infection medscape order minipress online pills, highly charged particle through the occipital cortex or the retina was estimated to be able to cause a light flash. First, the lengths of past missions are relatively short and the population sizes of astronauts are small. This section presents a description of the studies that have been performed on the effects of space radiation in cell, tissue, and animal models. There are several nuclei or centers that consist of closely packed neuron cell bodies. The most numerous of the neuroglia are Type I astrocytes, which make up about half the brain, greatly outnumbering the neurons. Neuroglia retain the capability of cell 196 Risk of Acute or Late Central Nervous System Effects from Radiation Exposure Human Health and Performance Risks of Space Exploration Missions Chapter 6 division in contrast to neurons and, therefore, the responses to radiation differ between the cell types. In recent years, studies with stem cells uncovered that neurogenesis still occurs in the adult hippocampus, where cognitive actions such as memory and learning are determined (Squire, 1992; Eisch, 2002). Accumulating data indicate that radiation not only affects differentiated neural cells, but also the proliferation and differentiation of neuronal precursor cells and even adult stem cells. Recent evidence points out that neuronal progenitor cells are sensitive to radiation (Mizumatsu et al. In contrast there were no apparent effects on the production of new astrocytes or oligodendrocytes. Measurements of activated microglia indicated that changes in neurogenesis were associated with a significant dose-dependent inflammatory response even 2 months after irradiation. These investigators noted that these changes are consistent with those found in aged subjects, indicating that heavy-particle irradiation is a possible model for the study of aging. Each bar represents an average of four animals; error bars, and standard error (Mizumatsu et al. These results conclusively show that low doses of 56Fe-ions can elicit significant levels of oxidative stress in neural precursor cells at a low dose. At doses 1 Gy a linear dose response for the induction of oxidative stress was observed. Particle radiation studies of behavior have been accomplished with rats and mice, but with some differences in the outcome depending on the endpoint measured. Sensorimotor effects Sensorimotor deficits and neurochemical changes were observed in rats that were exposed to low doses of 56 Fe-ions (Joseph et al. Doses that are below 1 Gy reduce performance, as tested by the wire suspension test. Behavioral changes were observed as early as 3 days after radiation exposure and lasted up to 8 months. Biochemical studies showed that the K+-evoked release of dopamine was significantly reduced in the irradiated group, together with an alteration of the nerve signaling pathways (Joseph and Cutler, 1994). Acute or Late Central Nervous System Effects from Radiation Exp posure Risk of A 201 Chapter 6 Human Health and Performance Risks of Space Ex xploration Missions Figure 6-5. They found that Fe-ion doses that are above 2 Gy affect the appropriate responses of rats to increasi work requirements. These observations sug ggest that the beneficial effects of antioxidant diets may be age dependent. Irradiated rats demo on onstrated cognitive impairment that was similar to that seen in aged rates. To determine whether these findings related to brain-region specific alterations in sensitivity to oxidative stress, inflammation or neuronal plasticity, three regions of the brain, the striatum, hippocampus and frontal cortex that are linked to behavior, were isolated and compared to controls. Changes in these factors consequently altered cellular signaling (for example, calciumdependent protein kinase C and protein kinase A). These changes in brain responses significantly correlated with working memory errors in the radial maze. The results show differential brain-region-specific sensitivity induced by 56Fe irradiation ([figure 6-6]). These findings are similar to those seen in aged rats, suggesting that increased oxidative stress and inflammation may be responsible for the induction of both radiation and age-related cognitive deficits.

Although other genes are the focus of study hiv infection essay buy cheap minipress 2.5mg line, research investigations have most consistently replicated the link between chromosome 6 and reading disabilities (Wood & Grigorenko hiv infection rate chart order minipress discount, 2001) hiv infection rate japan discount minipress uk. The primary emphasis of neuropsychological research concerning dyslexia has focused on the language cortex of the left hemisphere of right-handed individuals stage 1 hiv infection timeline generic 2 mg minipress with mastercard. For most people, the planum temporales of the left and right hemispheres are asymmetric, with the left planum temporale being larger than the right (L R). Neuroimaging shows that individuals with dyslexia often exhibit left-right planum temporale symmetry (L R), or reversed normal asymmetry (R L). However, the precise relation of atypical symmetry to dyslexia awaits clarification. Regional anomalies of the brains of dyslexic individuals are also associated with differences in brain activation as revealed by cerebral blood flow. Further evidence for disruption of the temporal and temporoparietal regions is provided by postmortem investigations of the brains of dyslexic individuals. Postmortem studies revealed neuronal ectopias (small loci of abnormally placed neurons, sometimes referred to as "brain warts") and cytoarchitectonic dysplasia (focal pathologic changes of cortical architecture) of the left plenum temporale, suggesting abnormal neural development, most likely between the 5th and 7th month of fetal gestation (Hynd & Hiemenz, 1997). During this period, the gyri are rapidly forming, suggesting that the origin of developmental dyslexia, whether genetically determined or a consequence of an insult, can be traced to a specific period of fetal development. However, not all studies have replicated the finding of atypical planum temporale development (Filipek, 1996; Rumsey, 1998), suggesting that other neural regions/systems may be involved in the etiology of dyslexia. Greater specification of the neural substrates that support phonologic processing is emerging (Horwitz, Rumsey, & Donohue, 1998; Pugh et al. The activation of these regions significantly correlates, suggesting a functional network supportive of reading. In contrast, individuals with dyslexia demonstrate reduced activation across the functional network, and the left angular gyrus fails to significantly correlate with the activation patterns of the other readingrelated regions. The latter finding prompted the investigators to conclude that the left angular gyrus of individuals with dyslexia is functionally disconnected from the other regions of the network. Insofar as the angular gyrus is involved in the cross-modal transformation of visual (written) information into linguistic representations, the disconnection would limit or distort input to the other regions of the left hemisphere necessary for readingrelated processing. Whether the functional disconnect is the result of anomalies in the white matter interconnecting pathways that link the left angular gyrus with the other reading-related regions of the left hemisphere, functional anomalies specific to the angular gyrus, or some other unknown set of factors remains to be determined. In a particularly well-designed study, Shaywitz and colleagues (1998) endeavored to identify the neural substrates that correlated with reading performance. The progression and type of tasks presented were as follows: (1) judgment of line orientation (visuospatial processing without orthographic demands); (2) lowercase and uppercase letter discrimination (orthographic processing without phonologic demands); (3) single-letter rhyming (orthographic to phonologic coding and analysis); (4) nonword rhyming (complex orthographic to phonologic coding and analysis); and (5) semantic categorization (orthographic, phonologic, and semantic analysis). The dyslexic group showed greater activation of the right inferior frontal gyrus as phonologic demands became more complex. This increased activation of the right anterior regions suggests that individuals with dyslexia rely on alternative or "spared" circuitry to process reading contents. Thus, individuals with dyslexia demonstrated decreased activation of posterior brain regions that encompassed both visual and language areas, and an increased activation of anterior brain regions. This activation profile may provide a neural "marker" for identifying individuals with dyslexia. The regional activation patterns of the children and adolescents with dyslexia differed from those of the nonimpaired readers. Based on the findings of these two studies and subsequent investigations (Shaywitz et al. Two of these systems involve the left posterior region, and the third involves the left anterior region of the brain. The first system, located in the left dorsal parietotemporal area (angular gyrus and posterior portions of the superior temporal gyrus), is believed to support the mapping of visual print to its phonologic representation. This word analysis system operates on individual units of words (for example, phonemes), requires attentional allocation, and processes information slowly. The second system encompasses the left ventral occipitotemporal region (portions of the middle occipital and middle temporal gyrus) and operates on the whole word (visual word recognition). This visual word system requires minimal attentional allocation and serves the automatic and rapid recognition of words.

Purchase cheap minipress. Basic Course in HIV - History of HIV | Center for AIDS Research.

When given a key hiv infection methods minipress 1 mg on-line, he or she may try to use it as a pen or a toothbrush and hiv infection rates by country 2011 cheap minipress 2mg fast delivery, in addition acute hiv infection symptoms cdc order minipress us, may not be able to pick out the correct gesture if shown by someone else hiv infection rates europe purchase minipress mastercard. Conceptual apraxia is not associated with damage to any one area, but is related to wider loss of semantic knowledge of tools and actions. Dissociation apraxia (formerly ideational apraxia) involves impairment in an action sequence. This type of apraxia can be witnessed in a multistage request such as, "Show me how you would pour and serve tea. Disorders of an action sequence may be caused by executive or frontal lobe dysfunction and a possible dissociation of action programs from language. In summary, the apraxias, as disorders of the how system of motor control, represent problems with the mental representation of actions. Although we present apraxia subtypes as independent entities, different types can occur together in the same person. The apraxias represent the most common type of motor problems treated by neuropsychologists, because they can occur due to a wide variety of cerebrovascular disorders (i. It coordinates reflex action and voluntary movement, is concerned with the timing of movement, and can differentiate movement frequency at a rate of 1/1000 of a second. It is also implicated in sequential aspects of motor learning, such as the steps required to learn to play the piano. The cerebellum is located posterior to the brainstem and inferior to the telencephalon (Figure 7. Cerebellar motor disorders are most often caused by structural damage caused by trauma or stroke. In essence, George had to figure out which abstract category the stimulus fit best. My responsibility was to present each stimulus figure, tell George whether he was correct, tell him when the category changed, and keep score. In total, more than 200 stimuli cards were presented, which fall into 7 categories. The first stimulus card was easy, and I told George his response, "two," was correct. As soon as I did so, he made a peculiar gesture, a kissing motion, in which he looked directly at me, raised his eyebrows, and shaped his mouth as if "blowing" me a kiss. When George was correct, he blew me a kiss, and when he made an error, he "gave me the finger. Midway through the examination, I decided to continue with the test, but I did ask George after the evaluation whether he knew he was engaging in these behaviors and if he was somehow angry with me. He informed me that he was aware of what he did, but that it seemed uncontrollable; "I just had to do it," he explained. He also told me that he was not angry with me and, in fact, enjoyed the testing and my company. Symptoms include facial and bodily tics, usually progressing from the head to the torso and extremities, as well as repetitive verbal utterances, including coprolalia (uncontrollable cursing) in approximately 50% of the cases (Newman, Barth, & Zillmer, 1986). Onset of the disorder is typically before age 10; symptoms vary in intensity over time and may be exacerbated by stress. This view is supported by findings of a high incidence of motor asymmetries on clinical neurologic examinations and abnormal electroencephalographic and computed tomography scans (Newman, Barth, & Zillmer, 1986). George, adopted in infancy, first displayed bizarre motor symptoms-jerking of his shoulders-at age 2. Later, he developed short barking sounds, repetitive movements of his facial muscles and arms, and finally, loud shouting of profanities. The bouts of impulsive and sometimes assaultive behavior became so difficult to manage in the classroom that George was taken out of school in the third grade. He had been hospitalized because he threw a brick at a passing car and chased it with an ax.

This site provides updates on dementia research antiviral medication shingles generic minipress 2.5bottles on-line, a virtual chat room antiviral vegetables discount minipress 2 mg amex, a dementia support group hiv infection rate liberia minipress 2mg on line, and other links side effects of antiviral medication best order for minipress. Overview Subcortical dementias are so named because, although these conditions often affect cortical areas and functioning, the structures that are prominently damaged are subcortical. The common behavioral feature characterizing these and most subcortical dementias is slowed cognitive and motor dysfunction (Neuropsychology in Action 15. What is interesting is the manner in which each disease affects the motor system in a different way. You can truly appreciate the complexities of the motor system by examining these diseases. The dementias we present in this chapter are progressive and involve multiple functional systems. Parkinsonism, like dementia, does not refer to a particular disease, but rather to a behavioral syndrome marked by the motor symptoms of tremor, rigidity, and slowness of movement. Mohammed Ali, the famous boxer, experienced parkinsonian symptoms (called dementia pugilistica) after repeated blows to the head (Figure 15. People most likely to have dementia appear to be those who have either had the disease for a longer period or are older at the time of diagnosis (Kay, 1995). This leads to speculation that Lewy bodies are either (1) indicators of a general disease process or (2) markers of cell death. The darkly pigmented, or melanized, substantia nigra is a midbrain structure that is part of a group of subcortical structures that collectively make up the basal ganglia. The basal ganglia, which reciprocally connect to the premotor cortex and the supplementary motor areas via the thalamus, largely function to control the fluidity of overlearned and "semiautomatic" motor programs (Bradshaw & Mattingly, 1995). Perhaps the reason that noticeable parkinsonian symptoms do not appear in older adults is because there is a "dopamine threshold," estimated to be breached at between 50% and 80% cell loss (Bradshaw & Mattingly, 1995), before symptoms appear. In this case, the referral is usually to help determine the presence or extent of cognitive decline. However, physicians may refer patients to either a psychotherapist or a neuropsychologist to aid in diagnosis before the "classic" symptoms appear. The patient may first sense vague aches and pains and wonder whether arthritis is developing. A general feeling of tiredness or malaise may come first, which could easily be attributed to overwork or "burnout. These symptoms may be met with assurances, a suggestion to undertake medical tests, or a referral to a psychologist to investigate possible psychosomatic problems or depression. The syndrome is produced by disorders affecting frontalsubcortical circuits, including lesions of the striatum, globus pallidus, and thalamus. Martin Albert and colleagues (Albert, Feldman, & Willis, 1974) reintroduced the syndrome into clinical neurology in descriptions of the subcortical dementia of progressive supranuclear palsy at Boston University in 1975. Substantial controversy centered on this syndrome when researchers first introduced it. Critics of the concept suggested that most dementia syndromes include both cortical and subcortical abnormalities, and that the clinical phenomenology was not distinctive enough to guide differential diagnosis. Subsequent experiences have helped to remold the concept and to account for these criticisms. Thus, although the pathology is subcortical in location, the dysfunction primarily affects the cerebral cortex. Thus, even within these mixed syndromes, it is possible to identify cortical and subcortical patterns of dysfunction. Researchers have increasingly documented the clinical features of subcortical dementia (Cummings, 1986). Slowing of cognition stems from the increased central processing time imposed by subcortical disorders. They show executive dysfunction, including difficulty with set shifting, as measured by tests such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test or Trails B of the Trail Making Test; reduced verbal fluency on tests of word list generation, such as the number of animals that can be named in 1 minute; impoverished motor programming, as measured by tests such as execution of serial hand sequences; and poor abstracting abilities when asked to interpret proverbs or to distinguish among similar concepts. Patients store information at nearly normal rates but have difficulty retrieving the information in a timely way. Thus, on tests of recall they perform poorly, but on tests of recognition memory they may perform in the normal range. Patients with subcortical dementia show neuropsychiatric and neuropsychological abnormalities. Motor abnormalities also accompany most subcortical dementias when the disease involves striatal structures, the substantia nigra, or globus pallidus.